The SEC is home to some of the most elite pitchers in college baseball. They don’t let just anyone take the mound in this league, which has produced some of the best pitching prospects in years.

What’s even more impressive, in my opinion, is the groundbreaking research coming out of the kinesiology departments at schools like Auburn and the University of Arkansas. These programs are leveraging markerless technology to provide in-depth biomechanical measurements of pitchers during live games. Until recently, this kind of data could only be captured using marker-based systems, which often weren’t applied to high-level throwers like those in the SEC.

Using a markerless system versus a marker-based one is like observing animals in the wild versus in a zoo. While they belong to the same species, their behaviors in such drastically different environments are unlikely to be the same. Similarly, pitcher mechanics may differ significantly between lab settings and actual game conditions.

Before we dive into the numbers, it’s important to emphasize that the findings we’ll discuss reflect averages across the 51 pitchers included in the study. Not everyone throws the same way. As the authors of the study noted, “there may be multiple movement strategies that achieve similarly optimal levels of performance.”

Here’s a link to the study by the way.

Size

This study analyzed 51 pitchers from five different SEC teams. On average, these athletes measured 6’2.5” tall and weighed 210 pounds—identical to the average height and weight of the approximately 660 pitchers on MLB rosters at the start of the 2023 season.

Shapes

By “shapes,” I’m referring to the positions pitchers’ bodies take at specific points during their delivery. This includes details like the degrees of abduction, rotation, or flexion observed in certain joints at key moments.

The key shapes examined in this study include:

- Peak Knee Lift

- Front Foot Contact

- Max External Rotation

- Ball Release

- Max Internal Rotation

These five positions are crucial for understanding the complex and rapid movement of pitching. To make sense of this intricate motion, I often rely on kinograms to break it down into visual snapshots my “simple human brain” can process.

Below is a kinogram featuring LSU’s Paul Skenes, arguably the most famous SEC pitcher in recent years.

Here’s a link to an article that describes Kinograms

In each of these 5 positions the researchers measured 10 different body positions that you can see below:

- Trunk rotation, flexion, & lean

- Pelvic & Shoulder Rotation

- Shoulder Abduction & Horizontal Abduction

- Elbow Flexion

- Stride Knee Flexion

- Hip-Shoulder Separation

Let’s start from the beginning of the delivery and we will see the angles and positions that produce the shapes needed to pitch at this level.

Peak Knee Lift

Here’s what the average pitcher looked like at peak knee lift on paper.

That’s a lot of numbers isn’t it? The far right column represents the range (plus or minus) from all of the individual pitchers used to create the averages that we see in the middle.

Let’s define these numbers by understanding what makes them positive or negative while also seeing what zero looks like. If you know and understand what all these terms are then feel free to skip this next section where I do my best to describe what they are and what makes them positive or negative.

Trunk rotation:

- Negative Values: The trunk is rotated toward the arm side (e.g., toward first base for a right-handed pitcher).

- Positive Values: The trunk is rotated toward the glove side.

- Zero: The trunk is squared up to home plate, a position that occurs later in the delivery.

At around -110 degrees in this study, the pitchers’ trunks are counter-rotated toward second base. For comparison, a right-handed pitcher squared up to first base would have a trunk rotation of -90 degrees. A more extreme example is Hideo Nomo, whose iconic windup likely featured a trunk rotation close to -180 degrees, as he squared up almost entirely to second base.

Trunk Flexion: A negative number here is when the trunk is leaning forward like we see below. A positive number is when the trunk is extended backwards. Zero would be straight. The average here at peak knee lift is -16.

Trunk Lean

This measures how the trunk moves side-to-side in the frontal plane.

- Negative Values: Leaning toward the glove side, often seen with an over-the-top arm slot at ball release.

- Positive Values: Leaning toward the arm side, which would typically occur with side-arm pitchers (not included in this study).

- Zero: The trunk is upright, with the head positioned directly above the hips and no lateral lean.

The average trunk lean in this study was 2.09 degrees.

Shoulder Rotation

This refers to the rotation of the throwing shoulder:

- Negative Values: The shoulder is internally rotated.

- Positive Values: The shoulder is externally rotated.

- Zero: The forearm is horizontal, parallel to the ground.

The average shoulder rotation in this study was 21 degrees.

Shoulder Horizontal Abduction

The average horizontal abduction was 54 degrees, which places the throwing arm close to the midline of the body—similar to the position of finishing a rep on a pec deck machine.

- Zero: Arms are straight out to the sides, forming a T-shape.

- Negative Values: The elbows move behind this midline, which typically occurs when the front foot hits the ground and the throwing arm gets deeper into the pec stretch.

The middle image below illustrates this concept more clearly.

Shoulder Abduction

Shoulder abduction measures the angle of the arm relative to the torso:

- Zero Degrees: The elbow is tucked in next to your side.

- 90 Degrees: The elbow is raised up and out, aligned with your shoulder.

Elbow Flexion

This measures the bend in the elbow:

- Zero Degrees: The elbow is fully extended and locked out.

- Close to 180 Degrees: The elbow is fully bent, such as when you touch your right hand to your right shoulder.

At this point in the delivery, the average elbow flexion was 116 degrees.

Stride Knee Flexion

Stride knee flexion refers to how bent the knee is during the delivery:

- Zero Degrees: The leg is straight, with the knee fully locked out.

- 115 Degrees: In this study, the average was 115 degrees, which is similar to the deep bend seen in a squat past parallel.

Credit – @aswansonpt

Hip-Shoulder Separation

Hip-shoulder separation measures the rotational difference between the torso and hips:

- Negative Values: The torso is rotated more toward the glove side relative to the hips.

- Positive Values: The torso is rotated more toward the throwing side relative to the hips.

- Zero: The torso and hips are aligned with one another.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way let’s move onto my favorite point of the delivery

Front Foot Contact

In this study, the first frame when any part of the foot hits the ground was defined as front foot contact. Some people like to go a frame or two further once the front leg starts to accept some force.

Here are the numbers:

Let’s look at some of the big players here.

Trunk rotation has not changed. It went from -110.84 to -110.32.

The blue line represents zero, while the black line shows the approximate amount of trunk rotation—just past 90 degrees in a somewhat counter-rotated position.

This image also illustrates what negative shoulder horizontal abduction looks like. The elbow is positioned behind the shoulder and closer to first base, which makes this a negative value. In the SEC group, the average was -23.85 degrees.

The elbow position is best viewed from above, as the forearm is relatively flat at this stage. Ideally, the forearm hasn’t “flipped up” yet as it transitions into external rotation. At this point, the shoulder rotation angle is approximately 37 degrees.

- Zero Degrees: The forearm is flat.

- 90 Degrees: The forearm is vertical.

The average of 37 degrees at this point allows ample room for the arm to load into its maximum lay-back position (max external rotation).

What I’m saying is: don’t let your arm externally rotate too much at this stage. If it’s too close to max external rotation before your foot hits the ground, you can’t fully maximize the stretch-shortening cycle, which is essential for generating power. In this 1990s image, Rick Mahler is externally rotated too much, too soon. His front foot isn’t even on the ground yet!!

Using this same picture we get an estimate of hip-and-shoulder separation too, which for this group is 57 deg.

Looking from the side provides a clearer view of other key measurements, such as shoulder abduction (red lines), which averaged about 83 degrees in the study. Paul Skenes appears closer to 90 degrees, which is well within the study’s range of ±13 degrees.

We can also examine stride knee flexion, which averaged 52.2 degrees (±6.65). Ideally, this is the most flexed position the knee reaches for the remainder of the delivery. The blue line serves as a reference point for the 90-degree mark based on the lean of the lower leg.

Max External Rotation

This is another crucial point in the delivery, defined as the moment the arm transitions from external to internal rotation. Capturing this position accurately is challenging, so use the highest frame-rate camera available if you’re analyzing yourself or your athletes at this critical stage.

Here are the numbers

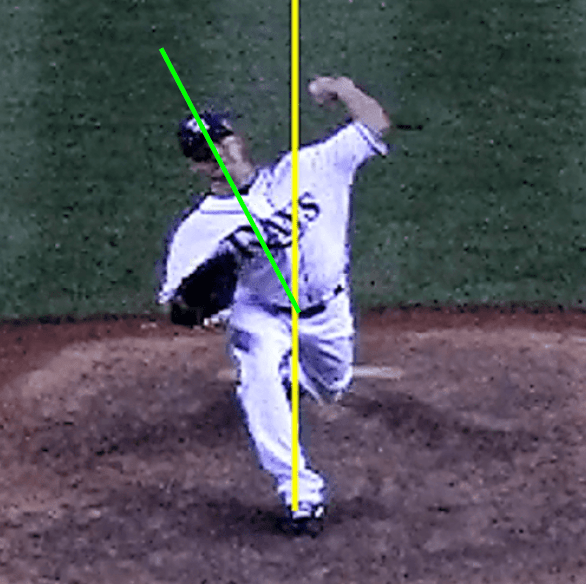

From the overhead view, we can observe the following:

- The trunk (green line) has rotated from -110 degrees to +1 degree, fully square to home plate during this brief phase.

- The hips (yellow line) have also rotated significantly, but to a lesser extent, moving from -58 degrees to +9 degrees.

We can see that the elbow is essentially in line with the shoulder, resulting in a horizontal abduction angle of just 1 degree. This alignment reflects the pectoral muscle reaching its maximum stretch during the scapular retraction phase. From this point, the elbow begins to move forward, driven by the powerful stretch-shortening cycle. These pitchers transition from -23 degrees of horizontal shoulder abduction at front foot contact to +5 degrees at ball release, showcasing the dynamic loading and unloading of the shoulder.

Here we see the forward trunk tilt progress from -14 to -20 degree as the spine waves towards home plate in the sagittal plane.

Trunk lean is a big player here. It’s at its most “negative” with a lean towards the glove side.

The average for horizontal shoulder abduction was -23 degrees, excluding side-arm and submarine pitchers.

This tilt changed significantly from front foot contact, where the average was +3 degrees. Knowing when to lean into this arm slot is crucial. Some pitchers reach these positions too early, which can lead to a loss of momentum and/or hinder the ability to effectively load and unload the muscles and tendons.

The key point here is the amount of external rotation at the shoulder, which is a defining characteristic of this phase of the delivery. It ranged from about 38 degrees at front foot contact to 180 degrees here. This gives pitchers roughly 150 degrees of range-of-motion to load the internal rotators of the shoulder as they approach maximum external rotation. Such a large range helps optimize the stretch-shortening cycle, which essentially “bounces” the arm back into internal rotation, maximizing power and efficiency in the delivery.

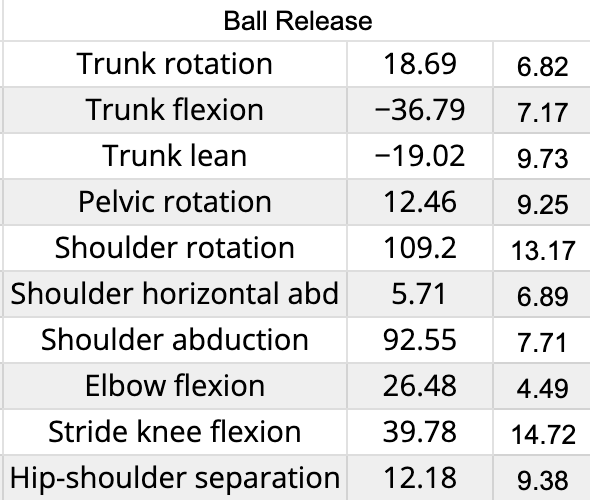

Ball Release

Here are the results of these SEC pitchers at ball release

Let’s begin by examining the stride knee. These numbers reinforce the idea that the front knee extends from front-foot contact to ball release, meaning the angle decreases over time. In this study, the front knee angles were as follows:

- 52.2 degrees at front foot contact

- 48.8 degrees at maximum external rotation

- 39.8 degrees at ball release

Most of the 12 degrees of extension occurred between maximum external rotation and ball release, highlighting that this action happens later in the delivery.

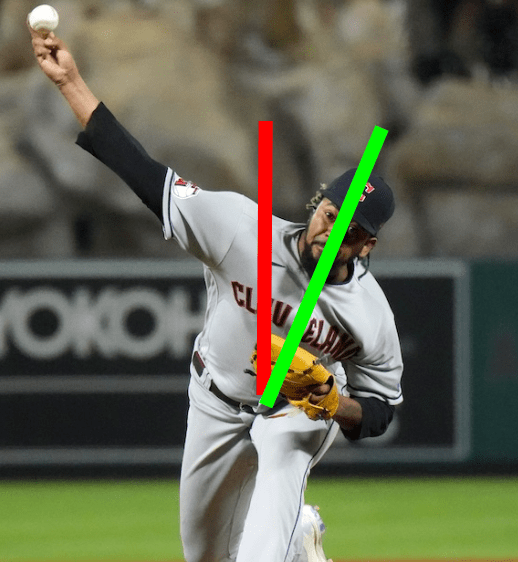

Here’s a snapshot of Paul Skenes at ball release. The green line represents his thigh position at front foot contact, while the red line shows the position at ball release.

The trunk tilt for this group actually started to straighten between maximum external rotation and ball release, shifting from an average of -23 degrees to -19 degrees at ball release. The trunk continued to straighten further as the pitchers moved toward maximum internal rotation, reaching -16 degrees.

Max Internal Rotation

This position is difficult to capture precisely with a camera alone, so I won’t dwell on it too much. Instead, I’ll leave you with an image of Paul Skenes at this exact point, along with the data from the 51 SEC pitchers in the study.

My plan is to revisit this study and dive deeper into the patterns identified by the authors. Understanding these key positions is just the first step. The real challenge lies in getting pitchers to execute these positions (i.e., patterns) with speed and power at the right moments (i.e., rhythm). In my opinion, this is the key to optimizing throwing velocity.

Thank for reading,

Graeme Lehman, MSc, CSCS

Leave a comment