If you want to use the vertical jump to assess your pitcher’s athletic ability, it’s more important to look at how much power they can produce rather than just jump height.

This distinction between relative and absolute power was the focus of this study that I’m going to break down. Click here to see the study.

To measure these two types of power, the researchers used two tools — a vertical jump on a force plate and a Wingate test on a stationary bike.

For the jump test, relative power was based on the height each athlete achieved, as well as how much power per kilogram of body weight they produced on the force plate. Absolute power came from the raw peak power measurement on a force plate.

When the researchers compared these results to pitching velocity, the amount of absolute force turned out to be the far better predictor.

The same pattern appeared with the Wingate test. Each athlete pedaled all-out for 30 seconds, and their peak wattage during that window represented absolute power. To calculate relative power, the researchers adjusted for body weight. So, if Athlete A (150 lbs) produced nearly the same wattage as Athlete B (200 lbs), the lighter athlete would have a higher relative score.

That relative score matters in cycling — which is why Tour de France champions tend to weigh around 140 lbs. He who can proiduce the most Watts/kg for the longest wins. But when it comes to throwing a baseball, absolute power reigns supreme.

This was the first study to use a cycling test to assess lower-body power in baseball pitchers. A previous study on handball athletes had already shown a positive correlation between throwing velocity and cycling power output, which prompted these researchers to explore the same relationship in baseball. (Chelly et al. 2010)

Interestingly, while cycling power was indeed correlated with throwing velocity, it wasn’t as strong a predictor as the vertical jump test.

Digging into the Jump Data

Let’s focus on the jump portion of this study. Here’s a quick snapshot of the 33 pitchers tested from Georgia Tech University:

- Age: 20.5 years

- Height: 6’1.5”

- Weight: 209 lbs

- Lean Mass: 175 lbs

- Peak Velocity: 92 mph

- Average Velocity: 90 mph

- Jump Height: 18 inches

The group’s average jump height wasn’t overly impressive at around 18 inches — even the top performer only reached 21 inches. That’s exactly half of this incredible jump by Georgia Tech alum Calvin Johnson.

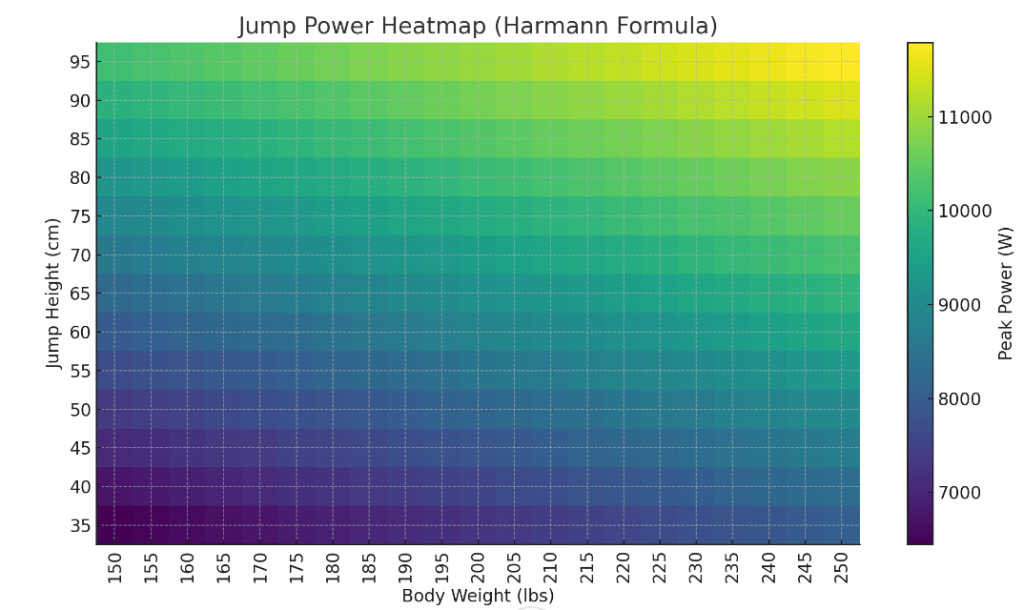

Even more remarkable? He weighed 235 lbs!!! That height and weight combo produces over 12,250 Watts of power using the Harmann jump formula. Absolutely crazy — pun intended.

Using that same formula, the pitchers in this study averaged just under 8,000 Watts.

Now, no one’s expecting college pitchers to match Megatron, one of the most powerful athletes ever, but the fact that his jump was nearly twice as high might mean the pitchers performed the test with hands on hips. The study didn’t specify.

This “hands-on-hips” method isolates lower-body power but drastically reduces jump height. As a side note, maybe we should think about how our arm path during throwing could similarly help us channel more power from the ground — but that’s a post for another day.

The authors reported that peak force, which again correlated with throwing velocity, averaged around 3,800 Watts. The Harmann formula provides only an estimate based on body weight and jump height, so the values won’t match a force plate exactly.

No matter how Peak Power was measured, it correlated with throwing velocity — while other measurements the authors collected did not:

- Jump Height

- Peak Power / Body Weight

- Sparta Score

All of these reward being lighter and jumping higher. The Sparta Score is a proprietary metric using a combination of several different metrics that a force plate can provide you with -read more about it [here].

Previous research backs this up too — showing no correlation between jump height alone and throwing velocity (Wong et al. 2010).

Why Absolute Power Matters

Here’s how the study’s authors put it:

“A greater body mass increases the total amount of potential energy that can ultimately be transferred to the ball, allowing for a higher throwing velocity given optimal mechanics.” (King et al. 2025)

In layman’s terms, “Mass = Gas,” as both overall mass and lean body mass showed a stronger correlation to throwing velocity than any other measure in the study, including peak power.

A Historical Comparison

This reminds me of a 2009 study that recorded jump numbers across all levels of four MLB organizations. Jump height alone didn’t separate MLB players from minor leaguers — but power output did.

“Vertical jump power measures were greater (p < 0.05) in MLB than AA, A, and Rookie players.” (Hoffman et al. 2009)

Here are the details:

They used a different formula (Sayers formula), which is why their power numbers differ. For reference, using that formula, the college pitchers would produce just under 5,000 W, while Megatron would still be in a league of his own at 9,250 W.

The researchers found that big leaguers averaged >4,500 W, while AA and below averaged <4,180 W — a statistically significant difference. Jump height, again, was not. (Hoffman et al. 2009)

Putting the Big in the Big Leagues

They’re bigger — and just as fast — meaning they can create more power. Power that, when used properly through sequencing and rhythm, can be applied to a 5 oz baseball.

Jump power could easily be added to Crash Davis’ long list of differences between minor leaguers and “the Show” in one of the best monolgues in cinamatic history.

What To Do About It

First, measure your current power ability using a jump test you can replicate consistently — so you’re comparing apples to apples.

Looking at an athlete’s power “formula” usually reveals where the low-hanging fruit is.

- A bouncy 150-lb athlete producing low power numbers (e.g., low 2000s) likely needs to add functional mass through hypertrophy training and nutrition.

- A 220-lb athlete who’s never touched backboard might need to reignite their elasticity with plyometrics or even some pickup basketball.

In most cases most athletes could use a bit or a lot of both. The conversation of how to best build both of these qualities is beyond the scope of this article. Deep dives into hypertrophy, strength, and plyometrics training would be helpful.

Check out the chart below for different ways to produce power. By being realistic about target body weight, you can estimate how high you’d need to jump to reach specific power thresholds.

Final Thoughts

Let’s be clear — jumping high and being heavy doesn’t automatically make someone a hard thrower. If it did, Megatron would be hitting 120 mph.

Throwing is a skill, built through years of refining how the body absorbs and redirects lower-body power up the kinetic chain.

If you have athletes capable of producing over 9,000 Watts of lower-body power (Harmann formula) but who don’t throw hard yet, that’s a clue. It tells you where to shift your focus — from the weight room to skill training.

Until next time,

Graeme Lehman, MSc, CSCS

References

- Chelly MS, Hermassi S, Shephard RJ. Relationships between power and strength of the upper and lower limb muscles and throwing velocity in male handball players. J Strength Cond Res 24: 1480–1487, 2010.

- Hoffman, Jay R; Vazquez, Jose; Pichardo, Napoleon; Tenenbaum, Gershon. Anthropometric and Performance Comparisons in Professional Baseball Players. J Strength Cond Res 23(8): 2173-2178, Nov 2009

- King BW, Snow TK, Millard-Stafford M. Peak Lower-Extremity Power Unadjusted for Body Mass Predicts Fastball Velocity in Collegiate Baseball Pitchers. J Strength Cond Res. 2025 Feb 1;39(2)

- Wong R, Laudner K, Amonette W,. Relationships between lower extremity power and fastball spin rate and ball velocity in professional baseball pitchers. J Strength Cond Res 37: 823–828, 2023. 26.

Leave a comment