The movie “Million Dollar Arm” was a feel-good story centered around a sports agent trying to find pitching talent in a country where baseball is barely played at all in an attempt to find “a diamond in the rough”. While watching, I couldn’t help but devise a set of tests and assessments that could have helped do a better job of identifying potential talent when it comes to throwing a baseball really, really hard.

The types of assessments that I am proposing would not make for good entertainment to the general population and would inevitably be cut from the movie. But if you’re reading this article these nerdy details appeal to you. So, unlike the movie where they only assess throwing, I am going to look at 3 additional yet important categories and tease out some important physical traits that are important to success on the mound.

- Anthropometrics

- Mobility

- Athletic ability

Before we dive into these categories let’s first explore the reason why we would want to look for throwers who don’t actually play baseball

Why Look for Throwers Outside of the Baseball World?

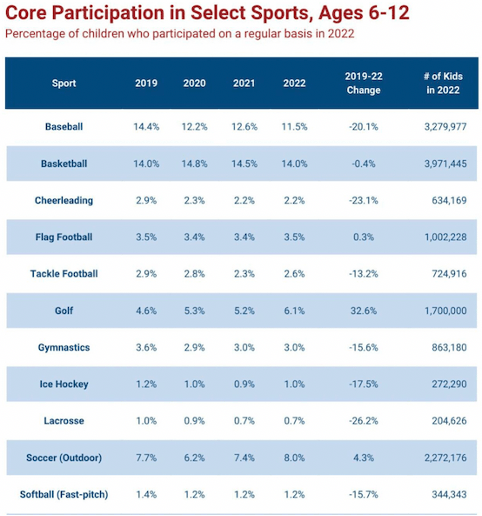

We want the biggest talent pool to draw from if we as the baseball world want the best of the best. If we only look at athletes who currently play baseball our talent pool is shallow. Since humans are designed to throw there’s potential to find premiere athletes who can launch a baseball out of their hand on every corner of this planet.

Looking overseas like they did in the “Million Dollar Arm” presents a lot of potential to deepen this talent pool. We should however maximize what we have domestically by developing grassroots and scouting into other sporting domains. While Baseball is immensely popular its numbers are dropping and not all of our best athletes are given baseball opportunities.

The high cost of travel baseball isn’t doing the sport any favors either when it comes to maximizing the number of participants.

Here are some situations where this might apply:

- Rural areas: kids that don’t live in towns large enough to play baseball or requires them to travel great distances.

- Inner City: kids that don’t have the chance to play baseball due to lack or teams or maybe the expense of travel teams won’t allow them to participate.

- Athlete’s that Play other sports: Kids often start playing whatever sport their friends play.

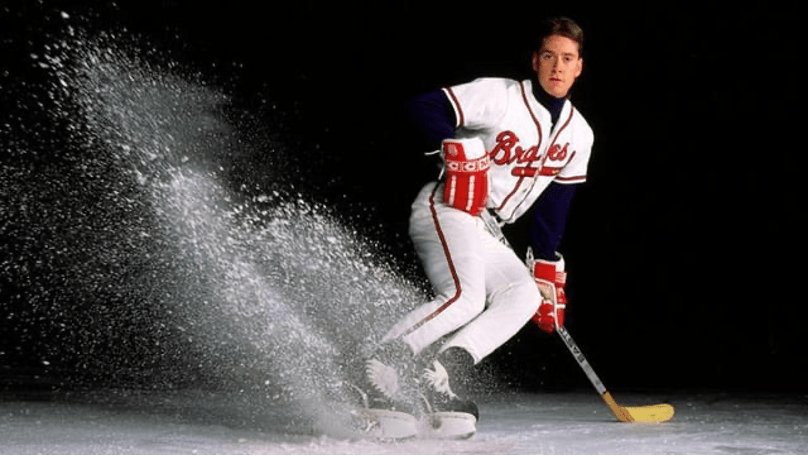

Personally, I have a lot of experience with this last category. I live in Canada where hockey is very popular and they get the lion’s share of the best athletes.

Hockey, like most sports now, is played year-round. This hording of talent has adversely affected the number of athletes who would have been exposed to baseball during the summer past the age of 12 which seems to be when the switch to year-round hockey happens.

Figure 1 – If Tom Glavine grew up Canada today we might have missed out on this hall of famer

Non-Baseball ID Camps

Below you will find the things that I think would be valuable to measure in this type of situation.

Here’s my criteria for selecting the tests and assessments

- Important

- Repeatable

- Quick & Easy

Anthropometrics

Let’s look at the frame of the athlete. Certain body proportions and limb lengths aid in throwing a something light really fast (i.e., a 5 oz baseball).

Let’s quickly look at some of the research done in this area.

Earlier I referenced the fact that humans are built to throw. A study out of Harvard identified three distinct physical features that gives our species mechanical advantages to throw. They are:

- Clavicle Width

- Long trunk

- Laterally facing shoulder joints

Here’s some research from other throwing sports as well:

- Cricket: high correlations between ball release speed and shoulder-wrist length and ball release speed and total arm length in cricket bowlers. Glaizer (2000)

- Water Polo: Taller, more muscular athletes with wider arm spans, broader humeri, and wider arms (relaxed and flexed) tended to throw with increased velocity. Martinez (2015)

- Water Polo: Biacromial breadth (shoulder width) shows a significate correlation to Throwing velocity. Ferragut et al (2011)

- Team Handball: positive correlation of the height and arm span to the ball velocity is consistent with previous studies involving male and female handball players. (van den Tillaar, R 2004, Vila 2012, Zapartidis, 2009)

Cool information but these types of throws aren’t exactly like what we see when we throw a baseball. In both water polo and handball, the feet aren’t even in contact with the ground while the throw is happening.

With cricket, the elbow has to be straight at ball release. So, the shoulder to wrist measurement in the Glaizer study makes sense.

*By the way, I don’t think that looking for baseball pitchers in the cricket world worked since the rules of that sport requires that the pitchers, or bowlers as they call them, does not allow any bend in the elbow. This takes external rotation, or lay-back, out of the equation. The throwing actions while similar aren’t similar enough*

Baseball Anthropometric Study

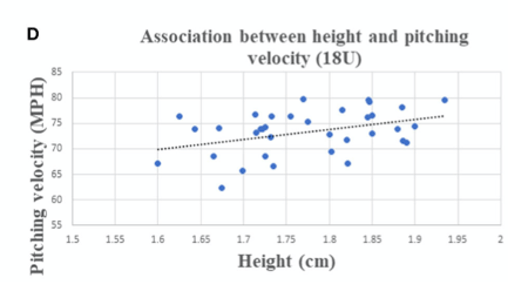

I’ve had to rely on information from other throwing sports because there isn’t a ton when it comes to anthropometric studies focusing on baseball. However, a recent study (Trembly et al.2022) did focus baseball players between the ages of 10 to 22. They looked at the following measurements and investigated any links between the results and their throwing velocity.

- Weight

- Arm Span

- BMI (body mass index)

- Waist circumference

- Upper arm length & girth

- Forearm length & girth

Researchers only linked height as a positive predictor to throwing velocity for the athletes in the 16–17-year range.

In this case all of the subjects played baseball. So, we can’t say that none of these measurements aren’t important when it comes to velocity because, as a group, perhaps they all have long arms, for example, which is part of the natural selection process to play baseball.

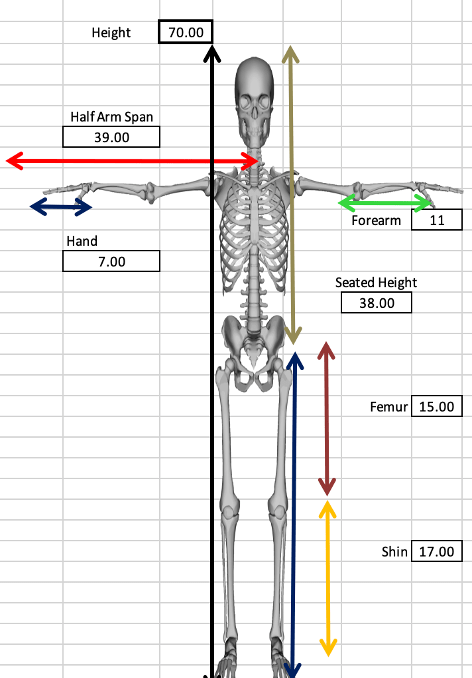

Based on this information, my own “gut”, and my criteria I listed, here is what I’d measure

- Standing Height

- Seated Height

- Half Arm Span

- Forearm Length

- Hand Size

- Shin Length

- Body Weight

From here I can get an overall idea of the athlete’s size and proportions. Here’s an example of what I produce with my pitcher’s physical profiling system

Size Now vs Size Future

This kind of information is even more valuable when we are trying to scout young athletes. The ratio of certain body proportion can give us clues about how big this athlete may get in the future.

The reason for this is that growth doesn’t happen uniformly across the body. “Growth Spurts” begin with the feet and hands, followed by the legs, then the arms, and finally the trunk. Even if we looked at the throwing arm, the more distal segments of the upper limb (hand and forearm) reach adult proportions before the upper arm (Jensen, 1986; Malina & Bouchard, 1991).

The seated to standing height ratio is the most commonly used assessment to estimate where an athlete is in their develop journey, or, how old they are biologically. An athlete’s biological age can differ from their chronological age by up three years, plus-or-minus.

“A child with a chronological age of 12 years may possess a biological age of between 9 and 15 years” (Borms, 1986)

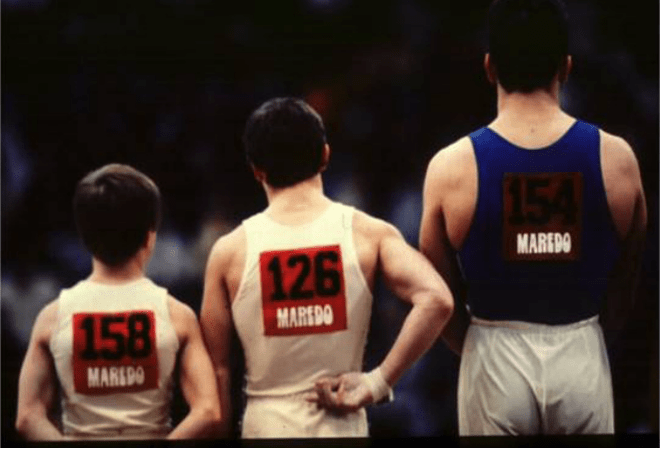

Figure 2: These 3 athletes are the same chronological age

If a kid looks to have pretty long legs relative to their overall height, then they have more growing.

The Cormic Index

The immature or biologically young athlete would be considered “brachycormic” on the Cormic Index which classifies people, mature and immature, based on their seated to standing height ratio. If your ratio is more less than 51%, you’d be called Brachycormic. If you fall between 51 & 53%, you’re a metricormic while those who are more than 53% are labelled at macrocormic.

I bring this up to stress that just because a young athlete has long legs now (brachycormic) doesn’t mean that they will grow out of it. Different populations tend to fall within certain portions of the Cormic index.

Africans have a tend to have long legs and are thus more likely to be brachycormic with a ratio of 0.51. Contrast this with Asian populations who typically considered macrocormic at 0.53 to 0.54 (Pheasant 1986). Obviously, there are huge variety within each segment of the population but it’s still worth considering in my opinion.

**Getting a look at an athletes fully grown family members can also be valuable – its even better is they are fast twitch type athletes – I guess I will have to add an assessment for the parents too!!**

That’s it for now. In part 2, I will explore the assessment of both mobility and physcial/athletic abilites.

Thanks for reading!!!

Graeme Lehman, MSc, CSCS

Leave a comment